Voter support of restrictions on oil and gas development largely depends on a combination of how close people live to wells and their level of partisanship, a new study on Colorado’s 2018 Proposition 112 vote reveals.

The findings were reported in “Partisanship and proximity predict opposition to fracking in Colorado,” an article appearing in the upcoming Energy Research & Social Science’s June 2020 issue and published earlier this week.

The study’s authors, Daniel Raimi, Alan Krupnick, and Morgan Bazilian used precinct-level data from election results as well as oil and gas activity to shed new light on what’s influenced the hotly contested ballot measures in Colorado.

Raimi, Senior Research Associate at Resources for the Future, told Western Wire that while a causal explanation is not attempted, and self-selection of voters and residency “could be playing a role here,” the “findings identify a strong relationship between partisanship, proximity, and support for oil and gas development.”

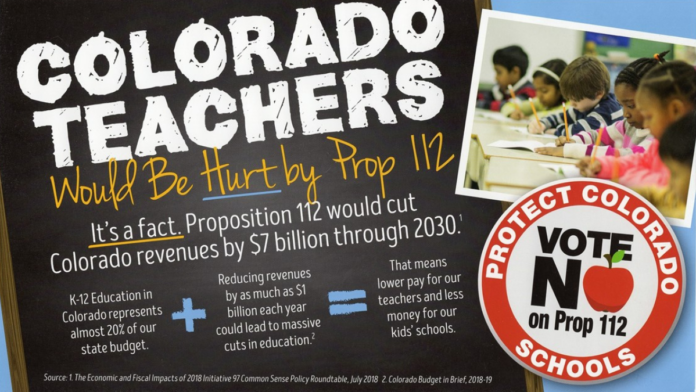

Colorado voters rejected Proposition 112 in November 2018 handily, 56 percent to 44 percent. The measure would have increased setbacks of oil and gas facilities to 2,500-feet from buildings like homes, schools and hospitals and sensitive geographic features like bodies of water.

In a series of tweets, Raimi expanded on the study’s key findings, which included the key relationship between proximity to drilling activities and relative levels of support and opposition to expanding restrictions on industry activities. “(1) Strong opposition to #fracking is mostly found in places where there is little to no drilling activity. Strong support for drilling is mostly found in the places that have the largest density of wells,” Raimi wrote.

“(2) This effect weakens, but remains significant, when we control for partisanship. Rs are more supportive of the industry, and Ds are more opposed. (in the weeds: our measure of partisanship is probably capturing other factors, such as rurality and demographics),” Raimi added.

“(3) Finally, support for drilling is weaker in places that have seen the fasting (sic) growth in drilling in recent years. The densely populated, rapidly growing, suburban Front Range is probably driving this. Plenty of folks there are not thrilled with the industry,” he wrote.

Comparisons of rates of growth in drilling were discernible at the precinct level, according to Raimi.

In his email to Western Wire, he added, “we observe in our study that precincts that have experienced the most rapid growth in drilling in roughly the last 15 years are typically less supportive of the industry than precincts where drilling has increased more slowly, stayed relatively steady, or declined.”

“Our hypothesis is that this reflects the growth of drilling in the densely populated Front Range, where–as you know–there has been considerable controversy surrounding the expansion of the industry. Additional research could test this hypothesis with more detailed data,” Raimi concluded.

The new setback distance would have excluded more than 85 percent of the state’s non-federal lands from new oil and gas development, according to a 2018 assessment by the Colorado Oil and Gas Conservation Commission (COGCC).

Raimi and his coauthors chose Colorado because it provided an example of policy choice in the form of a direct vote in 2018 and the state had time to experience the positive economic output of the expansion in oil and gas development.

“Colorado is a particularly interesting example for several reasons. First, some areas have decades of experience with oil and gas development, while residents in other regions are new to the industry,” the authors wrote. “Second, oil and gas development is occurring both in major metropolitan as well as rural regions where socioeconomic, geographic, and political conditions vary substantially. Although some localities in Colorado have sought to restrict or even ban fracking, the state as a whole has enjoyed the economic benefits of increased development,” they added.

Previous work studying the relationship between policy preferences and resident attributes found that “personal trust in the oil and gas industry plays a larger role in shaping perceived benefits and risks than factors such as proximity to drilling activity or political affiliation,” and that risk perception and political affiliation overall influence support for industry restrictions. Policy outcomes, such as higher energy costs, also strongly influence public policy support, with higher costs driving down support for expanding oil and gas restrictions, the authors noted.

The authors concluded that political affiliation was a key factor, and the maps showing areas of heavy support or opposition tended to fall along partisan lines—heavily Democratic Boulder, Pitkin, and San Miguel Counties supported Proposition 112’s expanded setbacks, while Weld and other oil and gas producing counties were substantially opposed to the measure.

“Consistent with survey-based research, our results indicate that partisan affiliation is a key driver of support for, and opposition to oil and gas development in Colorado,” the authors wrote.

Raimi and his coauthors pointed to the political balances in states similar to Colorado—those with Democratic majorities and governors—like New Mexico or California. Legislation at the state level, such as Colorado’s SB 181 in 2019, would look to restrict development or provide local authorities to enact their own restrictions. States with Republican majorities have passed state pre-emption rules that prohibit local restrictions, they wrote.

Raimi cautioned that the bottom line—perceived economic benefits sway residents’ preferences more than perceived risks. “At the local government level, the large majority of bans on shale development have occurred in regions with little or no oil and gas production. There are only a small number of cases in which local governments in regions with substantial levels of production have taken major steps to curtail drilling,” they wrote. That includes Colorado Front Range municipalities in recent years, but not the state as a whole in 2018.